The Western medical system is caught in a frighteningly mechanistic view of the world. Its narrative goes something like this: Organisms are built like machines, and we can understand them by breaking them down into their component parts and studying each one. Only by gaining such an understanding can we hope to treat the diseases and conditions with which the body is afflicted.

Needless to say, there are major flaws in this way of thinking. New revolutions in scientific and medical thought continually demonstrate that biology is vastly more complex than what our current theories and systems can account for.

We have a long way to go before we fully understand how to heal the body.

One stumbling block to true healing is the Western medical belief that the body is incapable of regenerating itself. Unlike bugs, lizards, and starfish, many doctors might say, human cells can’t just grow back once they’ve died.

But exactly the opposite is true: the human body is profoundly regenerative. While we may not be able to grow back appendages that have been lost, the regeneration of cells is absolutely central to the continued functioning of the entire body.

This cycle of shedding old cells and growing new ones is obvious in some parts of the body, like the hair, skin, and fingernails. But many other parts of the body are capable of regeneration too: joints and cartilage, the liver, the heart, insulin-producing beta-cells in the pancreas, and even many kinds of hormones.[1]

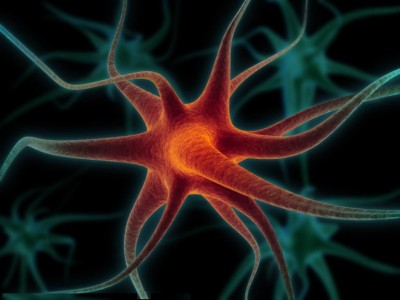

Volumes could be written about all the different kinds of cellular regeneration in the body, but let’s focus on one kind that doctors and researchers refused to believe in for most of modern medical history: the regeneration of brain cells and other nervous tissue.

The discovery of neurogenesis

Until very recently, almost the entire medical community firmly believed that brain cells simply cannot be regenerated. This doctrine was first articulated in the early 20th century, and vehemently defended by its proponents thereafter.

An MIT researcher named Joseph Altman published animal studies demonstrating the formation of new brain cells in 1962, but his work was ridiculed and ignored (other pioneers suffered a similar fate). Not until Professor Elizabeth Gould’s work, which she undertook throughout much of the 1990’s, was neurogenesis accepted as a provable phenomenon.[2]

Now that mainstream medicine is finally finished mocking it, neurogenesis has become one of the hottest topics in neuroscience. In the last decade, researchers have discovered that neurogenesis holds the key to understanding and treating cognitive degeneration, anxiety, depression, and many other mental disorders.

It was once thought that cognitive degeneration was a simple inevitability of growing older (in fact, many mainstream organizations still maintain that Alzheimer’s cannot be prevented, treated, or cured). Similarly, mental and mood disorders are treated as simple chemical imbalances that can only be remedied by lifelong attachments to pharmaceutical drugs.

But with the rise of research on topics such as neurogenesis and epigenetics, medicine is shifting toward the viewpoint that environmental factors and lifestyle choices play a more prominent role in maintaining your brain’s regenerative potential than ever thought before.

This means that you have much more control over your cognitive (and overall) health than mainstream medicine would like to admit.

Help your brain cells help you

Studies have firmly established a direct link between neurogenesis and trophic factors, tiny proteins that help form, maintain, and expand connections between neurons.

If your body and brain are lacking in these helper molecules, neurogenesis slows or even halts—which leads to cognitive decline, depression, and all sorts of other problems. In fact, researchers have found that prescription antidepressants work for some people not because they increase serotonin (it turns out that this model of depression is almost completely wrong), but because they increase levels of trophic factors when taken over time.[3]

Remember, though: antidepressant usage comes with a whole host of short and long-term side effects. There are much better, safer ways to increase trophic factors naturally.

Meditation and mindfulness practice works wonders for the brain. This is because stress inhibits neurogenesis more than almost any other factor, and meditation is one of the most powerfully stress-relieving practices available. Studies show that meditation leads to increased levels of trophic factors[4] and even increases grey matter density.[5]

Exercise is perhaps the single most effective way to increase neurogenesis. Running and other intense modes of activity have been shown to increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) glial cell line-derived trophic factor, both of which fuel the fire of neuronal regeneration.[6] A team from the University of Marland even showed that sexual activity buffers against the damage caused by chronic stress and increases neurogenesis.[7]

Diet. Many foods have been proven to increase neurogenesis, including turmeric, ginseng, ashwagandha, and even coffee. In general, eating a diet rich in detoxifying foods and cutting out refined sugars and processed foods is the way to go. And even the way in which we eat can be helpful for your brain. Studies demonstrate that healthy forms of calorie restriction, such as fasting once a week or fasting daily between certain hours (known as intermittent fasting), can increase the number of newly generated brains cells and induce the expression of BDNF in rats.[8]

By making these proper lifestyle choices, you can ensure that your brain retains its regenerative abilities—and thus its optimal functioning—well into old age.

References

[1] http://www.greenmedinfo.com/blog/6-bodily-tissues-can-be-regenerated-through-nutrition?page=1

[2] http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/the_reinvention_of_the_self/

[3] http://www.jneurosci.org/content/20/24/9104.full

[4] http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v16/n4/box/nrn3916_BX4.html

[5] http://www.psyn-journal.com/article/S0925-4927(10)00288-X/abstract

[6] http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v2/n3/full/nn0399_266.html

[7] http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/01/how-sex-affects-intelligence-and-vice-versa/282889/